the questions, vol 1: commercial rap and rap commercials

incoming: more rap nerdery. I promise I'll let it go after this (or at least take a break lol), and write about trains or something. in the meantime, here's the first installment of a new series.

How much money do you think fashion labels, car companies, shoe manufacturers, and liquor purveyors owe rap musicians? What order of magnitude should this debt be measured on; hundreds of thousands, millions, or perhaps billions? What I’m getting at is this: when was the last time you heard a brand name on a rap record, or saw a brand worn by a musician on Instagram, in a music video, at a performance….? I’d wager pretty recently.

Commercial rap is more than commercially successful; its central conceit is advertising, selling more than a personality or a lifestyle but a whole litany of products. How often do we think about how much commercial content we consume in music? How long have we been subject to being advertised to, and why is rap seemingly the only genre this occurs in? Should artists be getting paid for their advertisements; should we be listening to music that signals to us to conspicuously consume? Fight Club’s Tyler Durden posited that late-capitalist existence is consumption in place of emotionality, masculinity, and sexuality; how did our music end up not just reflecting, but actively perpetuating this reality? Is it a coincidence that rap, a genre formerly critical of the music industry and capital writ large, delivered from the pre-ecclampsic womb of underdevelopment and underinvestment, became mainstream at the exact same moment that it sold out in its lyrics, materializing its largest profits once it materialized itself?

What primarily irks me is all the damn ads in the lyrics. Nelly has two songs about Nike sneakers, that are unfortunately catchy and produced simply: Air Force Ones, on his 2002 album Nellyville (7x platinum), and Stepped on My J’z, on 2008’s Brass Knuckles (a highly underrated project, especially if you like the Neptunes sound (pprrz pewrrr pzzzrwwmt)). Jay-Z has countless unpaid sponsorships in his lyrics, most notably dissing an imaginary player on ‘Imaginary Players’, who asked him what the difference is between a Mercedes Benz 4.0 and a 4.6 (in case you wanted to know, it’s like 30 to 40 grand cocksucker, beat it). Six years later, Jay alternately praises and disses brands to Show U How (to do this, son!): his jeans ain’t Diesel, nigga they’re Evisu; and we don’t drive BMW X5s, we give them to baby mommas (in favor of Porsche Boxsters and Mercedes Benzes, the 600 not the 500, as well as G-wagons shaped like Kansas Chicken snackboxes). Rick Ross named his record label imprint the ‘Maybach Music Group’. Gucci Mane titled himself after the haute couture Italian brand; Lil Pump’s Gucci Gang became one of the most-hated songs of 2017, but got airplay and was promoted as a single as Gazzy Garcia described his amassed luxury (and tallied over 615 million streams on Spotify alone); Future just fucked your girl, if your name is Scottie Pippen, in some Gucci flip flops. Big was all about Versace; was he copying Pac’s style? Tunechi was blowing blunts down in Polo drawers; Polow tha Don produced a string of hits in the mid-to-late aughts with a string of rappers, including Juelz Santana; 2Chainz got horsepower with all this Polo he’s got on. Did the late Pop Smoke need to make a chorus on one of his biggest records (breaking a then-nascent Brooklyn Drill scene) shouting out Mike Amiri and Christian Dior? Would your dawg do it for a Louis belt? Or would you sell drugs and tally up thousands before running to Jacob the Jeweler to play which hue’s the Jay-Z bluest? Is your closet so full of Bapes it’s like Planet of the Apes? (fun related fact: supposedly, the Pusha T/Drake beef traces its origins all the way back to a dispute over payment for a Neptunes beat, and to who wore Bape first). Run-DMC at least got paid for their record, My Adidas, netting the group a reported million dollars in the bank for the promotion of their favored shelltoes (with chunky laces, or not laced at all please and thank you); however, this might all be Run-DMC’s fault. Their song was the first to prominently feature a brand name in its title, and likely kicked off the branding epidemic which followed.

Are you annoyed, yet? That’s partly the point; I’m unfortunately not done.

Rap has even, and perhaps especially, advertised its penchant for gunplay: 2Pac’s fo-fo’ll make sure all your kids don’t grow; Future’s Draco is sitting next to his bookbag, 21 Savage’s .223 will make a nigga back it up (pause), Jadakiss knows your man really wouldn’t like the Beretta (but he’d hate the mag), and I can’t even count how many Glock references exist in hip-hop history. It’s understandable that many musicians hail from a background where they were exposed to and perhaps participated in gun violence, leading to its inclusion in their lyrics; but it’d almost be reasonable to assume that Glock Ges.m.b.H. or Magnum Research, Inc. maintained partial ownership of Def Jam considering how much free marketing they’ve received on wax. This is not to indict rappers on weapons possession charges, or to say that they shouldn’t speak on what they’ve lived through; but, why mention brand names specifically?

Eventually, hip-hop caught enough steam and commercial success for rappers to be treated like celebrities, thus involving them in the typical celebrity trappings: most notably, getting paid to appear in advertising spots for brands (a step forward?). St. Ides had legendary tv commercials, featuring performances from the likes of Warren G, Method Man + Raekwon (with fucked up fronts) + Ghostface of Wu Tang Clan, Cypress Hill, Biggie Smalls, EPMD + Ice Cube, and ‘Pac + Snoop. Joe Budden rapped and recorded a commercial for a workwear outlet in Jersey City; too many artists to mention appeared in Beats by Dre promos (which also featured products heavily in an assortment of music videos). Eminem became clay putty in the hands of Brisk; Drake became a robot subsisting on Sprite droplets; 50 Cent conducted an orchestra playing ‘In Da Club’ off a bottle of Vitamin Water. I’d be lying if I said a lot of this wasn’t enjoyable to watch, and besides plenty of other entertainers entertain commercial deals—maybe all these forays can get a pass. (should they though?)

Following hip-hop’s endorsement deals following in Run-DMC’s footprints, and amidst great financial windfalls, rappers finally set out on their own business endeavors. They could effectually print free advertising for their new money schemes on CDs and sell them to us for $10-$15 a pop; we were paying to get advertised to. The Roc-a-Fella crew would no longer wax poetically on the subject of Cristal, following Jay-Z’s purchase of competing champagne label Armand de Brignac (aka Ace of Spades); he would later acquire part ownership of new cognac label Dussé as well, if he do say so himself. The Roc also owned Armadale Vodka, bottles of which former label executive Dame Dash would shake in music videos; the label would simultaneously wander into the fashion world with Rocawear and the S. Carter line. Sean ‘Puffy’ Combs has a 50% profit share deal with Ciroc and now owns half of Deleon Tequila, in addition to founding the premium clothing label Sean John. Wu-Tang created Wu Wear; 50 Cent sold G-Unit clothing; Tyler the Creator still owns Golf Wang (and has launched a new high-end brand, Golf Le Fleur). Pharrell and Pusha T both have deals at Adidas for their own apparel, as did Kanye West; Pharrell also owns the Billionaire Boys Club/Ice Cream label, while Kanye founded and created the most successful rap fashion endeavor of all time in Yeezy brand.

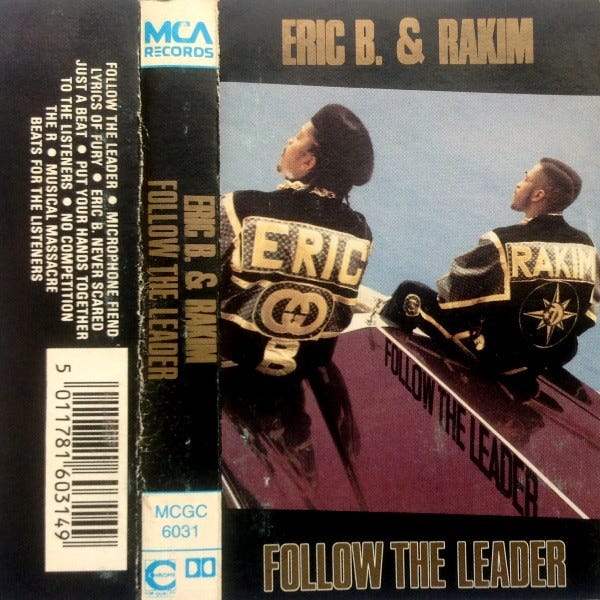

Music videos perpetuate the same farce of commerce visually, via commercial placements of vehicles, clothing, and even choice of locations; album covers often do the same, rappers sporting jewelry and designer labels. Dapper Dan apparel used to grace the covers of luminary acts. While trading one brand for another is hardly a progressive move, at least Dan’s appropriation of luxe labels into his own ready-to-wear lines was distinctively black, and his practice of making blown-out repeated-logo prints is almost a satirical commentary on materialism and logo worship itself.

When did all of the advertising just become background noise to us, like analog noise artefacts pressed into wax or picked up on tape? Is it even noise, or is it the signal we’re in fact meant to be listening for? I’m personally sick of ‘Versace glasses, Sick of slang, Sick of half-ass awards shows, Sick of name brand clothes, Sick of R&B bitches over bullshit tracks, Cocaine and crack, Which brings sickness to blacks, Sick of swole head rappers, With their sicker-than raps, Clappers and gats, Makin' the whole sick world collapse’. The continuous drivel of ad after ad after ad feels like I’m listening to a podcast with those stupid embedded scripted ads for dick pills and eBay car parts read by the hosts. This shit bogs us down in mad material shit, making us all fiend for the paper; when will we break the fuck out?

Hip-hop culture now is nearly synonymous with black music, but that wasn’t always the case; the amorphous labels that were previously applied to black artists, from Rhythm and Blues to Race records, to Urban music and back to R&B (before once more landing in Urban), encompassed everything from jazz to the blues to rockabilly to rock to Philly soul, the Motown sound, disco, quiet storm, dance and house and techno; none of this music endorses or embraces consumption with nearly the same gusto and fervor as rap does.

Moreover, hip-hop doesn’t have to look like this: prior to the branding epidemic, rappers mostly made club and dance records, before gaining consciousness (‘The Message’, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five), turning to the streets (‘P.S.K. What Does It Mean?’, Schoolly D), becoming Afrocentric, self-conscious, self-effacing (‘Tennessee’, Arrested Development and ‘Me, Myself, and I’, De La Soul), and exploring the vulnerability and haunting nature of those same streets we previously found ourselves on (‘Mind Playing Tricks on Me’, Geto Boys). Even in the midst of hip-hop’s marketing successes in the mid to late ‘90s, smaller venues and independent labels like SOB’s and Rawkus Records fostered a bubbling roster of acts who questioned the order as currently established and focused their message on politics, love, blackness, and everyday life. From Little Brother to Mos Def, to De La Soul and the Pharcyde, to Slum Village, and even artists who broke bigger like Common and The Roots, there is a vast tradition of our music being used to communicate, share stories, develop awareness, and just have fun. This ‘underground’ does still exist, in some shapes, forms, and fashions: many of these artists are still putting out music or supporting fresh artists, and newer acts like MIKE, Navy Blue, Earl Sweatshirt, Mavi, Armand Hammer, the 1978ers, the Globetroddas, and many, many more, are still making music that is beautiful, complex, fun, and warm just like we are. Is it necessary for our music to subvertise to us, or for us to listen to music that contains so many references to clothes and cars and so little emphasis on love, care, and joy? Wordplay, rhyme schemes, sheer verbal creativity, a revolution in sound (and sound manipulation, vocal recording, etc): all bent into service of capital in exchange for popularity.

?uestlove has surveyed and compiled an excellent body of research on the phenomenon of ‘black cool’, and its decline as an extant cultural aspiration and philosophy following hip-hop’s overtaking of black visual and auditory aesthetics. ?uest has even supplied representative figures who personified this suaveness, a stultified heat: Miles Davis, Prince, Sly Stone; D’Angelo could probably slip in here, as could Marvin Gaye. Has black cool faded immodestly into black ostentatiousness? Capitalism may possess the power to swallow and make profitable every natural product under the sun, including critiques of itself; from pro-blackness, have we fallen to the cultural conclusion that as everything is subsumed into commerce, we too should become commercials?

Finally: does this even matter? Everything else in our lives is heavily commercialized, and it’s not like we as people aren’t materialistic; it’s nearly impossible not to be, especially considering the droves of ads we consume on a daily basis just existing on the internet. The music industry made its product accessible to us for fractions of a penny on the stream; maybe the unseen price of this is the advertising we must abide, even after paying monthly for the service. But why aren’t musicians, or even labels for that matter, getting paid? Conspiracy theorists have formulated a story that explicates the increased violence in hip-hop as it passed through the mid-1980s, and exploded into the ‘90s: rap labels invested heavily into private incarceration facilities, and thus promoted music that advocated violence, to instill aggression in and detail violent acts for listeners. This was all done in hopes of landing more and more people in their newly owned prisons, to turn a buck not just on the artist but on the vulnerable consumer. While this is not verified, and not even all that credible, the idea that labels would invest in products and then market them to us in their music is certainly not incredulous.

In Black Against Empire, a historical account of the rise and fall of the Black Panther Party, authors Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. argue that critical concessions to the black community at their most heightened revolutionary aggression dissipated the potential for real change as people accepted a compromise of state programs (e.g. affirmative action for employment and college admission). Did the music industry do the same once faced with productive and community-building blackness in our music, shifting our gaze instead towards all that glitters (and is not gold) and towards the violence we experience? Or was this compromise instead made by our musicians, faced with unseen riches and the desire to keep the spoils for themselves?

To quote Shawn Carter, freestyling a Nas diss on a Nas beat, while telling him his baby mother sucked him off in his Jeep, formerly of Marcy Projects and 560 State Street, tossin’ ‘round nickelbags and now the New York Knicks, currently running a cryptocurrency education project with low attendance in those same projects: where do the lies end, where does the truth begin?