But graf, it can't save you

I published an essay on graf/street art in Boston Art Review's new print issue last week! below: mostly short stories & vignettes; reflections on the clearest visual form to me as a "writer"/writer.

Cans crack against each other’s half-emptiness in the homie’s bag, mixing peas rattling and clattering against metal enclosures as we step off the red line train in Central Square. Stomps up steps, boots on brick, and we arrive at Graffiti Alley. I wait and watch in awe as his piece finds refinement.

The homie had been writing for a few years longer than me, and he’d been teaching me little shit (“don’t add all those damn tricks to the tag,” “never write over another writer,” “right in front of the CCTV, you fiend?”) here and there. He’d been caught, narrowly, tagging choice words near his local PD’s precinct office, and wanted to make sure I wasn’t making the same mistakes.

In the alley, he completes a piece he’d started yesterday, commemorating fallen soldiers here and abroad. From Palestine to Prospect Street, martyrs in the struggle abounded; near the tail end of his letters, he threw up our children’s names and their children’s names, side-by-side.

He put his cans down ten minutes later, only acknowledging the outside world once he’d left his letters how he liked them. A firm, congratulatory hug, a nod, and we packed his paints up before jumping back on the red line towards Dorchester.

Cross-country, in the loud and heavy heat of LA in August, ***** explains his vision for a throw-up that politicks; he writes ******, at once a catchy disyllabic that explains its own power. Two years since we’d last truly got to business, four since we’d first started talking about writing, we were finally getting up together. His understanding of what and where to place our transgressions to property belied his circumstantial depth. He was born and raised in LA, where graffiti entered its United Statesian historical context as informal demarcation and claimant of land by territorial militants in the early 20th century; his understanding of how we use public art to police ourselves, as we are policed ourselves, filled in my politics of place and aesthetic like a fat cap shading the inside of a hollow.

I made sure to only pack earth tones for the trip, to not go over anyone or anything, to nod my head out of deference if ever my eyes met another’s.

I stopped by a gallery show in the South End this past winter (neighborhood: invisibilizing, show: suprising!) after my curiosity’d been piqued by advertisements proclaiming there’d be an exhibition celebrating Boston graf legends and street art history via fine art production. I knew a few heads from here or there, but was mostly lost in the mix; I tried to find and question artists and writers to learn what we were convened for and how they approached taking their style from the streets to the page, or to the canvas, or to puppetry.

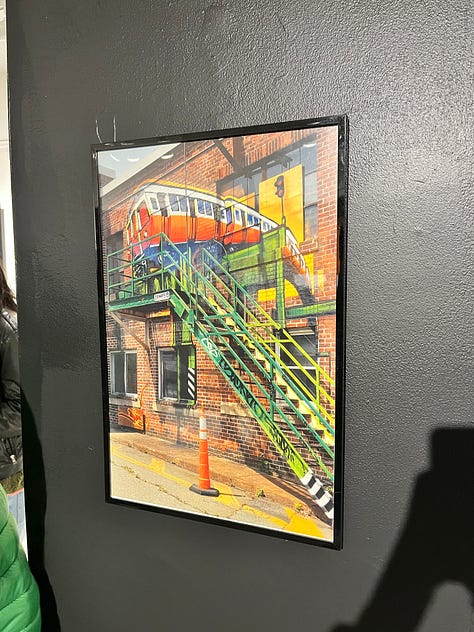

Many of the works in the show paid homage to graffiti’s early history on the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority’s old Elevated Orange Line. The first great loss many writers suffered was the demolition of the Elevated Line in 1987, considered by graf historians Caleb Neelon and Roger Gastman to be the first real home in Boston for the production and circulation of graffiti. Writers who lived along the line and contributed to its visuality in the South End and Jamaica Plain were venerated as a class of their own; Peters Park, about five blocks away from the show’s location in the South End, used to be a graf hot spot in large part due to its proximity to the old Dover stop on the El.

Nevertheless, Boston graffiti lives on and reproduces itself—while no longer as predominant in Jamaica Plain, for instance, hubs for writing and piecing have emerged in alleys in Back Bay, under the highway interchange between the South End and South Boston, and in parts of Fields Corner and Allston Village which have not yet been subjected to large-scale redevelopment.

A European writer, more toy than myself, asked me what neighborhoods would be good to get up in, and mentioned wanting to write himself into Roxbury and Dorchester: neighborhoods he could not and should not claim, neighborhoods which should not be bombed and should instead do the bombing. I redirected him towards Allston’s transplanted walls/streets/people, and towards Brookline, as more appropriate stomping grounds—an admonition from graf writer William “Upski” Wimsatt (author of Bomb The Suburbs and No More Prisons) passed through me to fuck up their shit, not ours.

I met an OG after this: a writer from the ‘80s, one of the first in Boston, and asked him what he thought of the event’s location in the South End, in a small arts district called SoWa (read: like SoHo, a developer’s naming convention applied to a formerly working-class neighborhood that has now been renewed out of existence). He remarked that many of the people present for the opening, on a local gallery First Friday event, were people who would have been robbed had they hung out in the neighborhood back when graffiti was predominant and when graffiti writers still called the place home.

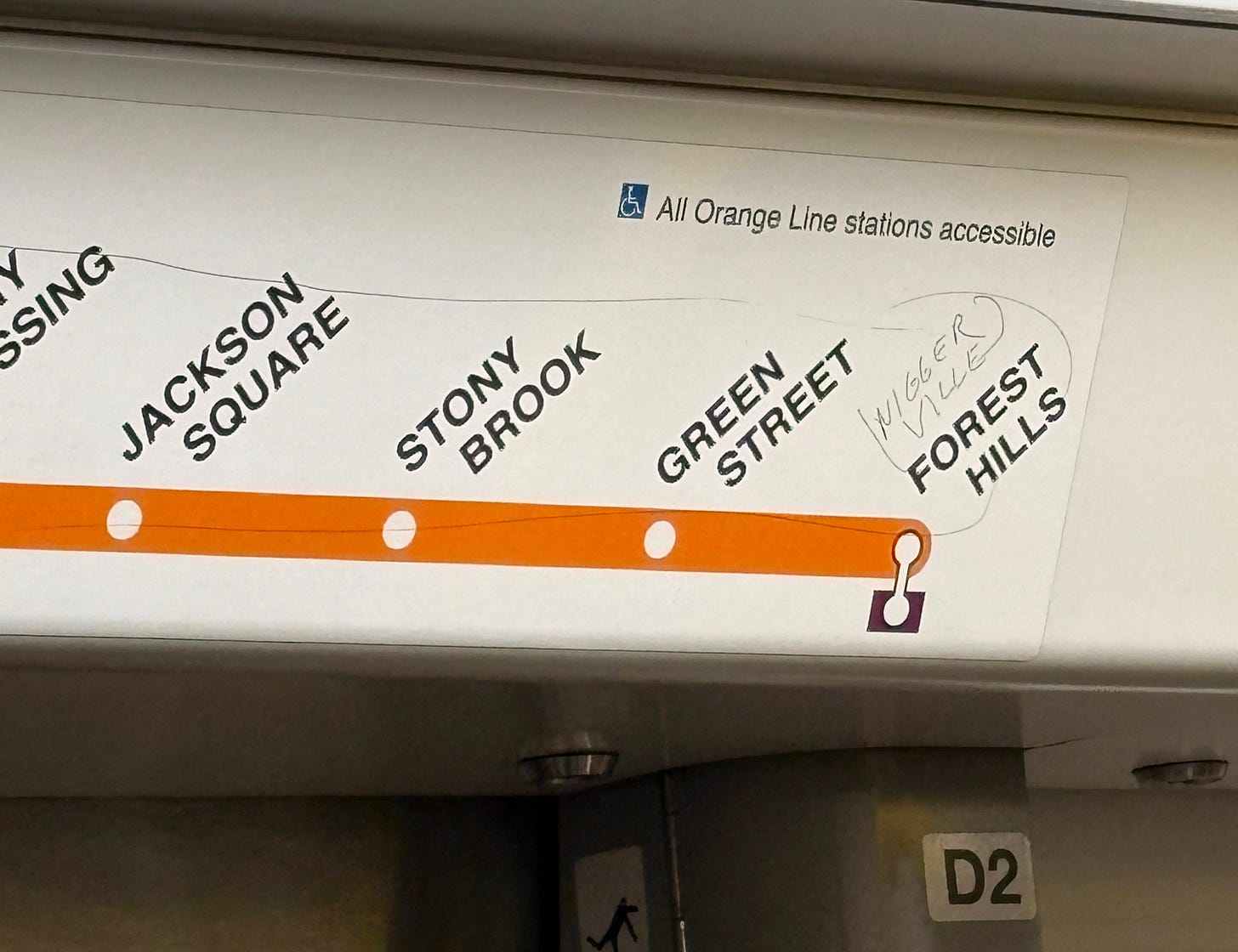

Riding the Orange Line this past summer on my way home, to Forest Hills, I looked up at the transit map and saw the entire line southwest of Mass Ave (covering the Roxbury and Jamaica Plain neighborhoods, home to many Black/Caribbean/East African communities), encircled with pen and lazily re-christened, “NIGGERVILLE.”

I thought about tagging over it, in true Boston graf style (its hip-hop-inflected variant emerging, in part, to cover racist spray-tagged epithets left during Boston’s busing days), but decided instead to simply Black it out.

I ran into another writer this summer: a boy saw me getting up on mailboxes downtown, and asked me what I write—I demonstrated, asked him his own byline, and he returned volley, slipped back into the night. I see his name everywhere now.

Walking over the short stretch of locks (as in locks on a channel, canal, or river) that link the West End of Boston, East Cambridge, and Charlestown over the Charles River, I happened across an electrical transformer box that’d been tagged into oblivion—a who’s who of hand-stylers in the city—and got out my own mop to let writers know I was around, too.

I briefly perched on a little safety gate that separated pedestrians from the transformer, to get up real quick, and noticed this old couple walking behind me slow to a stop. Their cutting eyes fixed on the back of my neck as I fiddled in my bag to find my marker.

They let me finish my tag before chastising through flat lips pursed into envelop slits: “you’re defacing private property!”

I replied through a beaming, full, and lightly-yellowed smile: “that’s kind of the point!”

I attended another gallery show in Cambridge, in Central Square, where a foundation was proud to announce their partnership with another foundation and a street arts collective and a graf crew in producing a show dedicated to “mural arts.”

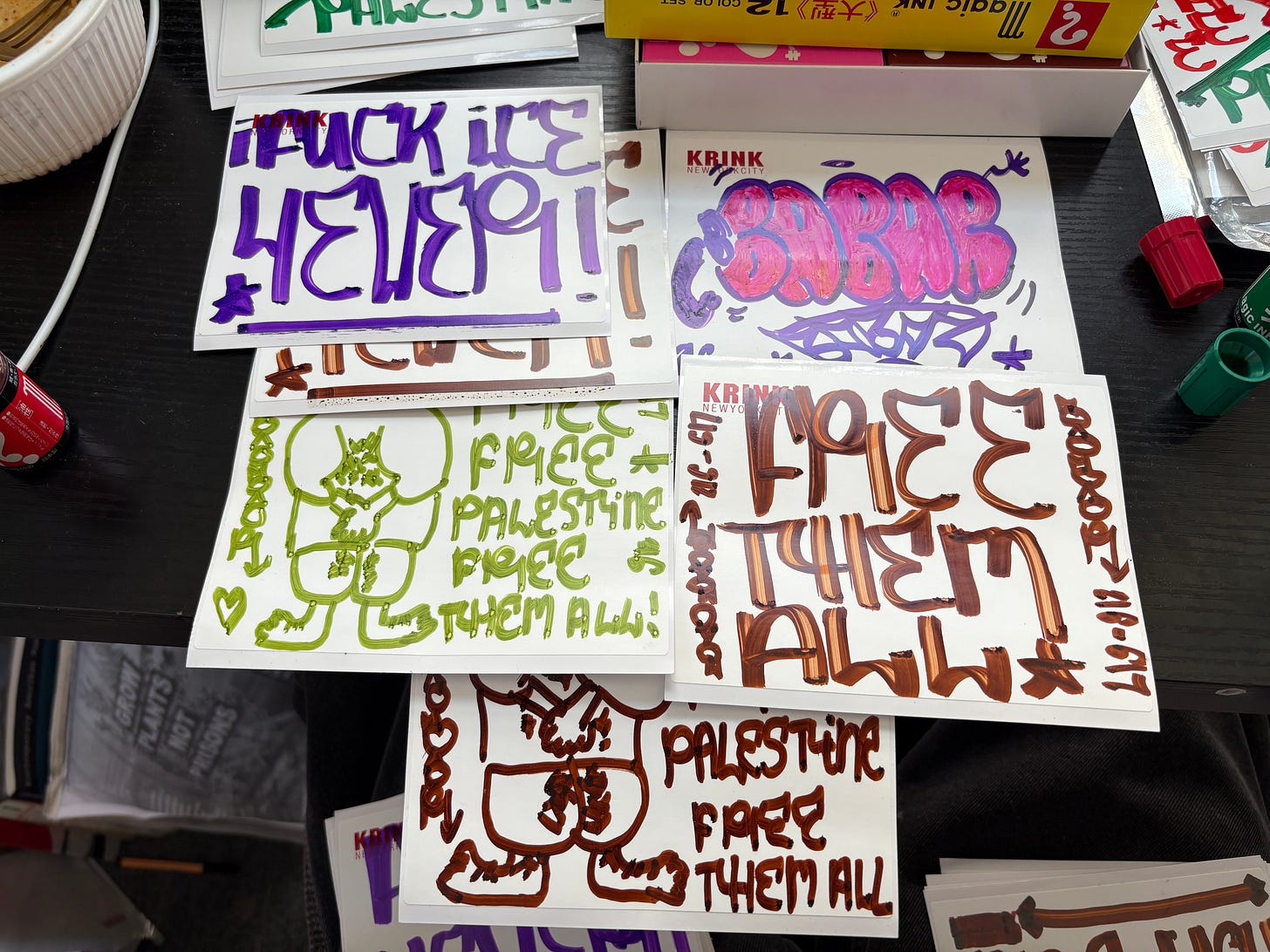

On my stroll to the show, I came across a fundraiser raising awareness and dollars for the Palestinian cause; a few artists had collected their wares to be sold in service of aiding families in Gaza, and in the adjacent alley the fundraiser offered an opportunity to spray messages of support or just to tag up and let folks know who was there in support of peoples arrayed against the axis….I promised myself I’d come back after my prior engagement.

I witnessed…elite capture at the gallery, or something more complicatedly confusing, anyway; street artists I loved from their pieces on public walls made inspiring work to hang on the gallery halls of a private donor who seems to move money towards worthwhile causes, in a room full of putters-on cloistered amongst opportunities. In any case, I said hi to who I knew, feigned interest in the work, and left promptly.

I came back to the fundraiser, an uneasy taste wearing away in my mouth and loosening off my tongue, and asked the purveyors of hope about the artwork they had up for sale; they recommended I pick up a can, instead.

My tags weren’t much; my message of solidarity was clear in language but lacking in flair. Still, a real writer sauntered down after I’d finished and complimented some of my letters (‘e’s as funky backwards threes), validated them, and told me I should keep working at my shit until I could do a throw, a wildstyle, a piece. I asked him what he wrote, and he asked me to follow and watch him work a throw-up from start to finish.

His words were few, our conversation intermittent, dotted with his interjections and notes on style:

see, this is how you connect your lines to flow them (ohhh)—(how did you feign that shine right there?) I learned perspective through practice

before he gave me a fist bump, greeted his old head who welcomed me incomprehensibly (sharing a laugh at a “Nobody Beats the Biz” reference), and passed me his number (***-***-****), told me his name (SMEK), and gifted me his black book.

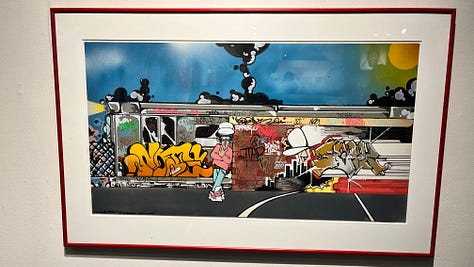

Legendary Boston graffiti writer and street artist Rob “NOTE” Stull showed work in that exhibition in the South End last winter, his last show before passing this spring. He had a new piece up, “Miss Liberty,” depicting a writer’s life and livelihood being stolen by the eponymous stand-in: a clear visual argument that Lady Liberty’s namesake principle only goes but so far.

Bending lyrics from Yasiin Bey’s “Hip-Hop”, writing will simply, “amaze you, praise you, pay you! Do whatever you say do; but Black it can’t save you.”

Buy a copy of Boston Art Review’s 15th issue here to check out my latest essay on graf, history/memory, and participatory arts in the City of Boston; or, take a look at the article online here.