dilla, drums, and non-linear time

just in time for the holidaysss a lil short read on some connected thoughts regarding music and time :)

The heaving, motion-inducing chops that open “Don’t Cry” (James Yancey aka J Dilla’s masterwork of a record on his final album in life, Donuts) bump into any sound-system or headset. Dilla’s kick drums laid over a sample of keys from I Can’t Stand (To See You Cry) plod into the listener’s ear before settling into their medulla oblongata to dictate their body’s cyclical rhythm for the foreseeable future, while the grunts and moans of The Escorts intimate a certain sensuality as the song eases into longer, slower cuts of the original record. Dilla’s tempos pull heads and necks across moods and memories, demonstrating an ability to play with how we experience time itself. First a quick waltz, then a slow ballad, finally a motile two-step, and then the cycle repeats...wandering drums hold all of this together in a way that makes sense, coaxing us into each new time signature and rejecting the quantization and formalization of time.

Jay Dee’s work enjoyed the informality of his drum kits and patterns--he literally produced with the quantization feature (akin to a ticking metronome for instrumentalists with the added feature of snapping drums into perfectly syncopated alignment) disabled on his drum machines. The rhythms of his records tracked his fingers on the pads of his Akai MPC as he willed songs’ time progression back and forth. ?uestlove likened his percussive work to that of a drunken toddler: his snares would be placed whenever they felt like coming while his kicks lull listeners into a pleasant lurch that recalls the imprecision of punk-band drummers. Yet Yancey still retained a certain soul and smoothness, witnessed especially in his neo-soul-inflected mid-career production (see: Sometimes - Ummah Remix, by the Brand New Heavies, or Got Til It’s Gone by Janet Jackson and Q-Tip). Whether a reaction to the super shiny, over-produced rap + rnb records of the concurrent Bad Boy era, or a more self-derived creative desire, J Dilla’s discography and credits attest to his proclivity to play with the procession of our internal clocks.

Musical experimentation with linearity and consistency in our experience of time remains fascinating to me; beyond just being fun, records like Dilla’s stretch the imagination and toy with expectations. There’s perhaps a too-easy parallel to draw between Dilla’s lollygagging drum programming and the notion of colored people time--however, there’s a reality there, which speaks to the governability of time and time zones vis a vis the illegibility of the marginalized. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man notes, “[i[nvisibility gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind.” This off-kilter situation in the scientism of Western time may be explained by alternative practices in the subaltern.

Africana disciplines of philosophy regard time as something much more mutable and moldable; communication with ancestors in healing practices amongst traditional Zulu healers of southern Africa signify history reaching immediately into the present tense. Moreover, Swahili in eastern Africa carry a conception of time known as Zamani, which regards the eternal past, present, and immediate future as all deeply linked and accessible to one another. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-5, a deeply ruminative work of anti-war fiction, considers time similarly through his employment of 5th-dimension-inhabiting beings known as Tralfamadorians: time is roughly another spatial dimension to them. Thus, everything that has happened, is happening, and will happen, all exist simultaneously. Tralfamadorians have the ability to traverse this time dimension as they please; there is no future, past or present, but rather a realm upon which time is constructed. To them, humans live on an unbending track which takes us through the events sequentially; however, I’d contend that this linear notion of time winds more than we think.

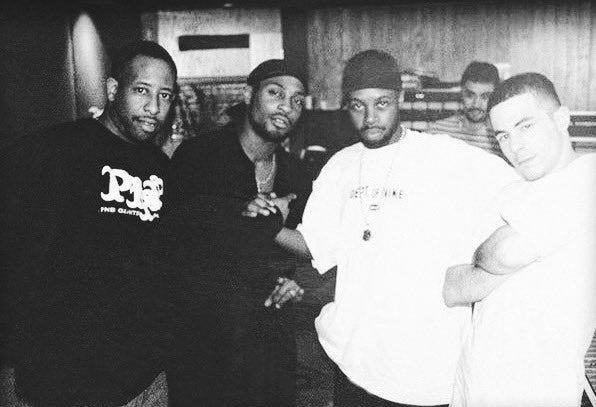

From left to right: DJ Premier, D’Angelo, James Yancey, Alchemist

Dilla’s unstandardized patterns, and those of his neo-soul contemporary D’Angelo (as well as his later collaborator and fellow sample-chopper Madlib), speak to a commonality in how our own hourglasses empty rhythmically; but not metrically. Whether via the industrial work-clock, or self-imposed deadlines and agendas, our metered progressions in life form a rigidity around time that doesn’t bear the emotionality of how we experience it: moments in exam rooms or on exhausting first dates at art museums last compounded eternities, while time with our loved ones or years of self-discovery slip through our fingertips as quick as sand. Contrary to the keeping of time across every device which has the capacity (fridges, really?), we don’t live metronomic lives. Moreover, memories and stories provide windows and passageways into the “inaccessible” past we worry about passing by, in the same way song refrains, codas, and samples resurface old moments in time through new, episodic lenses; the metaphorical track which we travel on can quicken or muddy, even loop.

To ignore how our ephemeral grasp on time’s passage resists structure is to give into the largesse of ‘scientific’ productivity, to cede enjoyment and pace to linearity and stricture. Fuck clocks and perfect drums; let us be and experience our limited lives on Earth the way we intend. To reference a Roy Ayers’ record sampled on Black Star’s Little Brother (produced by none other than James Yancey himself), we ain’t got tiiiiime to be tireeeedd...we got a long, long way to go :’).