Barbershop 4: the one where LeBron doesn't understand the music industry

I love LeBron probably more than the next man but...c'mon dog

Moving to Cleveland in 2006, one year before the Cavaliers finally fought through the Eastern Conference Finals’ ghoulish perennial favorite Detroit Pistons, and staying in the city’s vicinity through 2017, after they’d taken us to three Finals in a row and finally delivered a championship to what was then the only home I’d ever truly known, I’d consider myself a LeBron fan. I more than understood and accepted when he took his talents to South Beach, welcomed him back when he returned home, and defended his legacy from Jordan nutriders and Kobe acolytes in Twitter replies and Instagram comments. So when his latest project (HBO-exclusive series The Shop) was announced in 2018, I was excited to catch new episodes of his conversational show centered around our supposedly heralded discussion forum within the Black (male) community: the barbershop. Celebrities swing by to chop it up with other guests and sometimes LeBron himself while getting fresh tapers and lineups, on a program which reclaims the media circuit for performers and athletes alike and allows them to speak freely (although to say ‘freely’ is to elide the celebrities’ own self-imposed bounds, and those of their employers; in today’s capitalized media landscape, speaking freely translates more so to speaking comfortably than to speaking candidly amongst the economically-able and media-scrutinized members of our denizenry); Donald Glover recently appeared on the show before deciding to circumvent even the façade of collegial discussion in his latest interview, conducted in Interview magazine by none other than: Donald Glover.

To watch The Shop, I pay for the most expensive AT&T plan available with the meager salary I collect from my monotonous ‘Research Project Specialist’ position at a faceless think tank; I like having unlimited 5G and a large repository of data banked for hotspot usage in case my wifi goes out and I need to log on to yet another work meeting which cascades into three more work meetings, culminating in a finalized task/memo/document to be shared at next week’s work meeting, but the most enjoyable part of this too-expensive telecom month-to-month contract deal that I’m currently behind payments on is the included HBO Max subscription. (This is made possible because HBO and a litany of other media properties under WarnerMedia, including the eponymous Warner Bros. studios, CNN, Cinemax, TBS, and the CW, were all wholly owned under AT&T’s corporate umbrella until April 8th, 2022, and have now all been spun-off into a new media merger called Warner Bros. Discovery (of which AT&T retains a 79% ownership stake)).

The latest episode of The Shop was also released in full on YouTube as a teaser; a few episodes each season are published for free, to entice viewers to pay the $10 to $15 a month sticker price for HBO Max and access to all of LeBron’s sometimes stunted discussions with some of the world’s biggest stars in television, music, and sports, as well as the back catalog of the United States’ second largest media conglomerate. LeBron invited to set some of his favorite musicians whose lyrics he never seems to quite recall to memory, Gunna and Rick Ross, alongside returning guest Steve Stoute (founder and head of UnitedMasters—more on this later), to have a conversation with series regulars Maverick Carter, LeBron’s high school teammate who now co-leads their shared media endeavour SpringHill Company, and Paul Rivera, who headed The Robot Company with LeBron before it got folded into SpringHill. There were others present on the barbershop’s set, but the bulk of the episode’s airtime was allotted to the interplay between these 5 men and LeBron.

Eventually (at around 18 minutes and 40 seconds in), talks turned to Rick Ross’ newly-minted independence from a major label, as he’s fulfilled his contract requirements with Epic Records, a subsidiary of Sony Music Entertainment; Maverick asks Ross how he feels about being done with his contract and moving forward with the ability to own all of his own music, before Paul Rivera asks Ross and Gunna if labels matter in music anymore—this is where the conversation, at least to me, finally materialized its temporal worth. They both answer that labels ‘most definitely’ matter (without explaining why) before Ross explains that artists must negotiate their terms with labels to eventually become profitable; artists typically start their contracts off in debt, and Ross believes that an artist taking a smaller advance, and working hard to release music, can overturn their disadvantageous beginnings.

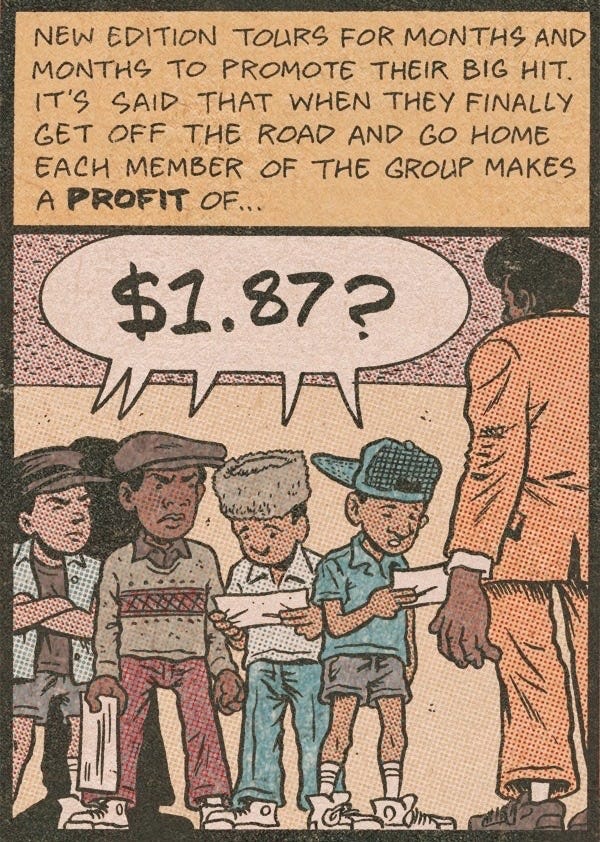

Steve Stoute then jumps into the conversation, to disagree with both artists; UnitedMasters aims to turn the music recording business on its head, by functioning similarly to a music label but with key differences. A typical music recording contract that an artist signs to a label will lend the artist money, an advance, against their projected album sales: what that means is that the artist signs for x amount of dollars, which typically becomes (part of) their budget to record and promote the albums they are contractually obligated to release under their new label. They are then required to pay this money back to the label via their album sales, until they recoup the loan fully. However: in signing this deal, the artist relinquishes their rights to own their own work—the label owns the physical recordings, and the right to re-release them and profit off them in perpetuity. On top of this, artists often signing publishing deals (to publishing companies which are largely owned by the labels), again for a large sum of upfront money, and sign away their rights to own the intellectual property of the lyrics themselves on their recordings as well as all lyrics they write, even for other artists. Moreover, the label receives the lion’s share of the proceeds from album sales, and the artist is expected to pay back the money they received not from the total income generated from the album selling, but from their percentage of the royalties. Typically, an artists’ percentage of royalties is around 15%, but can range higher, maybe to around 20ish percentage points. So, for an artist like Yasiin Bey, aka Mos Def, who put out the greatest album of 1999 (Black on Both Sides), if his advance (loan) was $500,000 then not only does he not own his own album, even if he paid back the loan in full, he had to make the money back not from each $10 sale of his album, but from the 12% royalty share he earned on that album. If Bey went gold with that project, which he did, then he sold 500,000 copies at $10 a piece and the album grossed $5,000,000, which vastly outpaced the loan amount that was owed to Rawkus Records (his label). However, 85% of that money was gone off-rip, sent straight back to the label and publishing companies (none of which counted towards his advance), so Bey only saw $600,000 of that, of which he still had to pay back $500,000. If the label offered tour support, then Bey wouldn’t have even reaped the full monetary benefits of performing his songs at concerts; and if Bey has a manager, then depending on the deal he signed with them (what percentage they’re owed, if they earn money off gross earnings or net earnings), he might end up in the hole off of a commercially successful album!

UnitedMasters seeks to upend this intensely overwrought and exploitative method of recording music by offering artists another way: UnitedMasters functions only as a distributor of music, and maintains that all artists signed to them retain full ownership of their master recordings and their publishing rights (as long as the artist hasn’t previously signed them away). They will promote and place music strategically, set artists up with technology officers and commercial deals, and help them succeed only in exchange for a percentage of the profits made off of endeavours through which UnitedMasters is directly involved. Since music labels no longer provide artist development, are not the sole outlets to produce and distribute recordings, and do not generally support artists in the ways they previously had, UnitedMasters essentially fills every important checkbox that a label would, but in a much more financially advantageous position for the artists they sign; they even offer advances!! And the industry standard delay of royalty payments doesn’t exist at UnitedMasters; artists receive their income in real-time, as their music sells and streams.

Thus, Steve Stoute embarks on an abbreviated version of his standard spiel, which I’d first heard him lay out on the Joe Budden Podcast one year ago, detailing how labels are mattering less and less and how artists can make it and thrive outside of the major label system where they don’t own their own music. Unfortunately, the direction of the conversation bends towards the ceaseless arc of industry as Gunna cuts in to explain his remarkably flawed understanding of labels as ‘business partners’ (the classroom equivalent of such a partnership would be a group project where your classmate provides money for you to buy the supplies, then you go out and buy the supplies, you put them together to make a diorama which earns high marks, only for that classmate to receive the grade you earned while you owe them back their money for the supplies you put together) and how he feels that artists who buck the system and say ‘fuck the label’ are shooting themselves in the foot. He goes on to say that labels ‘take chances’ on artists, and it’s up to the artist to make the money back (completely neglecting to mention the fucked-up way artists have to recoup, and that labels sign artists who already show commercial promise and don’t take risks, especially not anymore). He finishes his statement by proclaiming himself the ‘contract killer’, and saying that he works his way out of contracts to get new ones issued on ‘his terms’. How exactly do you work your way out of a nearly impossible trap set so the label makes money first and foremost, at the artists’ detriment? And what are his terms? Do they involve ownership of the music? Such a prospect is quite literally impossible in the major label system, yet it’s arguably the most important financial and creative aspect of producing music. Owning the music is what allows royalties to be paid on the artist’s terms, and what allows them to license records to be placed on soundtracks, to be re-released or re-mixed/mastered and receive new streams of income, to be sampled and receive a percentage of the new record’s proceeds.

However, even this proposed solution is only a half-step towards parity in the music industry; no record is composed solely by the named artist, who is still often paid the most in comparison to all other individuals involved in the actual making of the music. Every artist receives help, from instrumentalists, producers, songwriters, or recording engineers (who ‘mix’ and/or ‘master’ the records, often placing and tweaking vocals and instrumental tracks to foreground vocals and solos, match tonality, bend basslines, and generally manipulate the recorded material to make it sound the way an artist or label wants it). This ‘help’ can make or break a song—songwriters and producers contribute just as much, if not more, than the artist themselves. These contributors are seldom paid royalties, typically only upfront money and at times even an hourly rate, which seems wrong; even if the ownership shares aren’t split completely fairly, why shouldn’t a producer or engineer receive points on the backend once an album or song hits digital service providers and shelves to be streamed and sold? Sometimes artists fail to even credit these integral people; Lauryn Hill was sued in 1998 by the New Ark Group, a musicians’ collective, after releasing her seminal solo album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and misappropriating credit on her album’s liner notes (incorrectly claiming that she wrote, arranged, and produced each and every single track). Twenty years later, Robert Glasper claimed once again that Lauryn treated those session musicians and songwriters unfairly, and that she treated her touring bands with a similar level of disrespect. Instead of banding together with their fellow musicians, artists pass the buck and fuck their underlings over.

Speaking of which, established artists will even screw new aspiring acts via an enterprise known as the ‘joint venture’ deal. Every musician that you see signing new acts to a label: from Jäy-Z’s early days at Def Jam signing Beanie Sigel + State Property, Kanye West, and Cam’ron + Dipset to Roc-A-Fella; to Rick Ross signing Wale, Omarion, and Meek Mill to Maybach Music under Atlantic Records; to Young Thug’s whole roster of young artists, including Gunna, signed to YSL under 300 Entertainment (which is owned by…Atlantic Records); are all signing them to deals wherein a large established act is able to create or import their own imprint label within their extant deal (or in a separate deal, in Ross’ case) and making money off of them. In turn, they split the proceeds from their signees evenly with their major label partner—this new label imprint is considered a joint venture, because the established artist and major label are now actually business partners, and their signees become the exploited classmates from my admittedly clumsy previous analogy. So the fucked becomes the fucker. Gunna might believe that he can turn around and sign acts under such an operation, as barbershop compatriot Rick Ross has and as Young Thug did with the proponent of P himself.

LeBron then expounds upon what he considers Gunna’s brilliant point, offering himself and his playing career as an example: roughly, LeBron details that rookie deals are capped and structured in certain ways such that an NBA team can’t pay a player but so much money in their first deal. However, if a player, such as himself, works hard enough and plays to their maximum ability, works out in the gym and watches film and does everything right, then they can eventually get a max contract as LeBron did, on ‘his terms’. Whose terms is it really? Is an ownership stake involved? Why couldn’t LeBron and other players follow through on Kyrie Irving’s astute proposal to initiate a stoppage of play/players’ strike during the politicized, pro-Black uprisings we saw in 2020, if players can work their way into deals that are on their terms? Is LeBron aware that NBA players at the very least have a players’ union, and that no such structure exists in the music business? How can a player ‘work their way’ into a position like LeBron’s? Is it even possible today?

Returning finally to the structure and concept of The Shop as a television program, and its proffered industry knowledge offered via the import of ‘having conversations’: are these conversations meaningful anymore? Especially when mediated through agglomerations of media conglomerates, overlaid atop one another like the shittiest corporatized interpretation of the fallacious ‘turtles all the way down’ argument. LeBron’s SpringHill Company producing The Shop while operating distribution via HBO, itself under aforementioned ownership by WarnerMedia (which used to own Warner Music Group, a record label conglomerate under which Atlantic Recordings owns Gunna’s records and co-owns Rick Ross’ Maybach Music Group ), fully owned by AT&T prior to a merger which is now mostly owned by AT&T, seems like an extremely corporatized, bordering on media-monopolized, manner of producing what is essentially promotional material for these artists’ previous and forthcoming efforts. As much as I love LeBron, and love the concept of cross-pollinating communication and interviews conducted by others within similar and disparate industries alike, it’s hard for me to not find myself skeptical of the final product.

Moreover, artists and athletes have become more and more cynical about their reception, and about their money: ‘branding’ has cannibalized personality, ‘content’ has anabolized art. The soul and meaning inherent to the music, movies, even teams that we loved is increasingly being sapped out of the cultural material we consume, as getting to the bag holds higher regard than creating impactful works.

What happens when the multimillionaire artists and athletes, who unfortunately form a sort of cultural vanguard for the Black community, falter in the face of monied interests and internalize its logics to become stewards of capital themselves?

Jäy-Z a.k.a Shawn Carter, an esteemed member of this vanguard, performed an unheard freestyle nearly three years ago at a concert he’d dedicated to his own B-sides (records which weren’t singles or even popular album cuts), which lit up social media as he forecast that Black people’s saving grace would be its talented tenth buying up land and gentrifying our own neighborhoods before white people could. Ignoring the impossibility of this proposition, and his serious misunderstanding of gentrification’s encumbent displacement: Jäy-Z had not ten years prior facilitated the gentrification of downtown Brooklyn, by moving the New Jersey Nets to the recently-constructed Barclays center and helping to coordinate Brooklyn’s attendant facelift. Thousands of working class Black and Brown people were pushed out of their own neighborhoods as rents skyrocketed and new housing complexes arose catering to a newer, whiter, richer demographic, while Mr. Carter reaped his sown seeds in the form of a newly-minted ownership share in the Nets; is this what he truly has in mind for our future?

Is there potential for a revolutionary Black culture anymore in the media space? Has celebrity worship and consumption subsumed culture into commodities and streams?

We are in dire straits, I’d say.