All Power to the People, Realized

A people’s power can be exerted over more than just their elected officials; democratized economies hold a liberatory key to justice and politics.

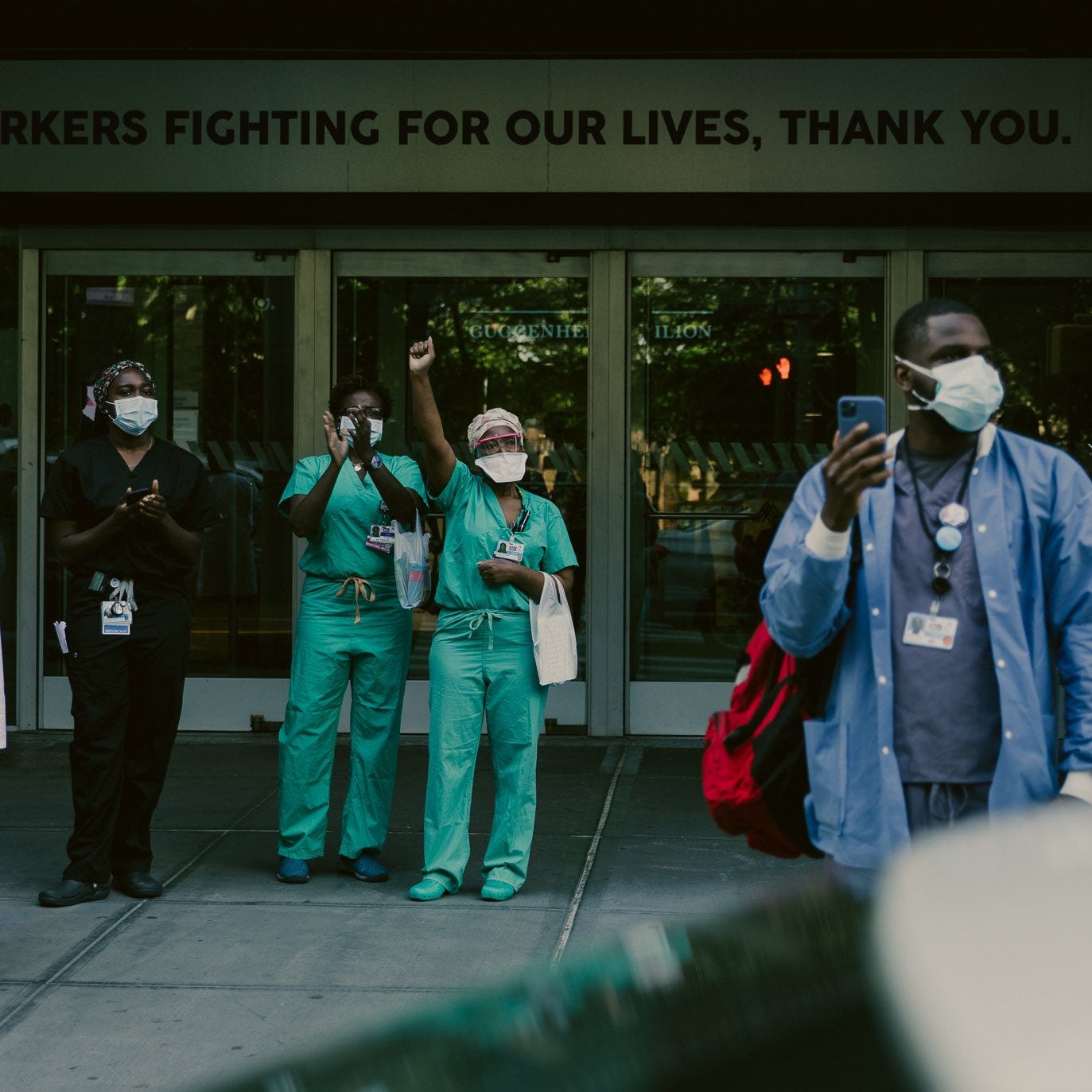

Chants of “Black Lives Matter!”, “Say her name!”, “No justice, no peace, no racist ass police”, are ringing out across the country in our streets and on our screens.

Recent police and vigilante murders of Black people have driven one of the largest mass movements in our history for Black lives and against white violence, with marches, riots, and occupations lasting months into the collective fight as people realize that we’re sick and tired of being sick and tired. As James Baldwin put it to us more than 30 years ago, “You’ve always told me it takes time...how much time do you want? For your progress?”

The supposed legitimacy of our political semi-democracy has long been under question but a renewed vigor has flooded the streets, our cities awash with a multiracial coalition fighting to extend the franchise to live free of state violence to Black and working-class people in the United States (and abroad, with protests in the U.K., across the E.U., and in Japan both relating to police brutality in their respective countries and in solidarity with black protestors).

This expansion of democracy to include the agency of Black people has come with calls to defund and disband police departments, especially upon finding out that police departments were funded at multiple (sometimes hundreds of) times the level dedicated to mental health services and public health, fair and affordable housing, there’s been an especially fierce uproar. How are these departments, the arbiters of this state violence, the most well-funded parts of our governments, over transportation infrastructure, housing the homeless, and other seemingly more pressing and less abusive measures to help city residents? And why aren’t city budgets controlled more directly by the taxpayers who fund them?

Defunding local PDs means extra cash flow, to be redirected into municipal funds for social programs, education, and housing. Yet, a certain violence has been perpetrated against black people via social and development policy as well (to say nothing of continually segregated public education and a school-to-prison pipeline), as city planners and real estate developers have all but eliminated Black people’s agency to live and stay where they wish in their own cities (via redlining and urban renewal previously, and through unaffordable new developments and gentrification now), as well as disemboweled local business and labor (through the aforementioned renewal and development). So, who gets to control forthcoming economic and housing development in our cities? Moreover, how can the current state of affairs be changed, and economic power be put in the hands of the people?

This issue of investment goes beyond defunding police; the abolition movement driving the advocacy and action for radically broad-based and deep upheaval in our justice systems also moves to divest from the prison and military industrial complexes, whether via tacit removal of funds invested in private prisons and military contractors or through pressuring corporations to stop abusing the carceral state and 13th amendment to enslave prisoners. But why are institutional investments and decisions controlled by undemocratically elected board members whose returns-oriented motivation instigates these abuses in the first place? Why aren’t companies, universities, and nonprofits under the control of the people who work for them?

We have bought into the paradigm of electoral democracy (however flawed) without a concurrent and respondent democracy in our communities’ economies. Economic democracy —built out of a politics of solidarity in communities coming together to make decisions for themselves, borrowing from Marx’s idealized worker struggle and from black socialists’ movement toward cooperative ownership for communal liberation (as embodied by outgrowths like the Young Negroes’ Cooperative League founded by George Schuyler and Ella Baker in 1931 around Harlem and the New Communities Land Trust in Albany, GA created by the Republic of New Afrika in 1968) — responds to the centralized, bureaucratic institutions which respond to developers and business owners over residents and labor by making the residents the developers, and labor the business owners. Accountability, so desperately called for by the frustrated and unheard and often difficult to maintain, is substituted with community control and participatory budgeting. Workers co-operatives, either through instantiation or buyout, comprise businesses which are wholly owned by the labor that runs them; decisions regarding capital are directly in the hands of the people who generate it, from investment (and divestment) to liquidation/redistribution: all of it it in the hands of the people. Housing co-operatives and community land trusts provide a similar liberatory element to their communal owners: from rent to management to new housing developments, all under the direct and distributed control of those who call the area home.

Manifestations of this people’s power exist in the US, both past and present (as the aforementioned worker's co-operatives and community land trusts + housing co-ops, but also in mutual aid, unions, and participatory budgeting) and are intimately related to Black movement politics: from the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, a community planning organization which owns a land trust in Roxbury, Boston which engages their neighborhood to make its own decisions about land use and development through claiming eminent domain on properties to be transferred into neighborhood ownership; to the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, a group of organizers fighting for tenant-managed housing and equity-based economic prosperity; and Banana Kelly, in the South Bronx, promoting health via new food outlets while buying up property from slumlords to develop safe and affordable housing units; as well as the Boston Ujima Project, which works as a democratic investment bank to fund local and worker-controlled business in Black neighborhoods of Boston; to Cooperation Jackson which is rebuilding an entire city around alternative + solidarity economics; to the aid professed and instilled by the Black Panthers and Young Lords from health clinics to education and the Free Breakfast for Children program (a precursor to the expansion of HeadStart), reinstituted now via city mutual aid networks in the midst of pandemic-induced unemployment and instability. And people are fighting for new incarnations of democratized investment alongside all of this (people’s councils on city government expenditures, i.e. participatory budgeting, the goal of People’s Budget LA, for instance).

The work being done by these advocates and organizers to truly empower communities and make people’s voices heard concerning the places they live is not just important to highlight, but necessary to contribute to as an extension of the liberation sought in demolishing oppressive institutions like the police. After diverting tax dollars away from what we act to abolish, the struggle can’t end with the buck remaining at the doorstop of unaccountable institutions and governments.

The meritocracies, technocracies, bureaucracies, the whole managerial class has proven time and again that it will not work for the people it is supposed to serve, instead treating them like unknowing subjects; an argument in favor of such a professional class which makes decisions for us is an inherently anti-democratic one which presumes people do not know what is best for themselves and should not hold control for themselves even though time and again through direct actions (labor strikes, marches + protests, riots + looting, mass demonstration in every circumstance) we demonstrate that we know and fight for exactly what we need. Such a position is roughly authoritarian in its implicit and unending trust of incumbent authority figures and its core belief that only those figures can adequately provide governance; paternalism without accountability, quite literally the instatement of and obedience to a ruling class. If we should not dictate our economies, should we not dictate our own governance? In principle, due to the states’ protection of private property which enables economy and due to the opacity of the state itself, this is often the result: because we do not own the physical capacities to make goods, provide services, develop land, the politics which surround these processes are largely inaccessible to us.

Community control is a central part of the Movement 4 Black Lives, and pushing for broader control of these institutions, from academia to local governments (where voting elects representatives but not the faceless bureaucracies which often mismanage our tax dollars and are harder to hold responsible), is necessary to truly seek transformative and restorative justice by directing our own funds. You cannot hold a corporation or institution accountable if their motives are profit or research driven, because these organizations are directly accountable only to shareholders and administrators: the work therein lies in changing the motives by changing who holds the power.

Imagine a world where we wouldn’t have to appeal to developers and alphabet soup city organizations for our freedom to stay and live where we want, where we could fund services in our areas and promote worker co-ops and local economies, because the people had the power; wouldn’t you love to live there?