aaliyah's second death, and the crisis of digital conversion and media commons

we're losing the culture!!

A couple of years ago, in the midst of getting paid for a summer research position in the brain and cognitive sciences department (which mostly consisted of me, staying in a house with a friend, slowly losing my mind, and committing wage fraud), I stumbled across the “song credits” selection in spotify; touch/click the three dots next to any given song, scroll to the bottom, and you’re golden. There’s an immediacy such an availability of information places on the songwriters and producers of a record, previously tucked away in liner notes and meticulously hidden behind the artists’ name and presence (particularly controlled by de-metastasizing record labels trying to promote themselves over their employees).

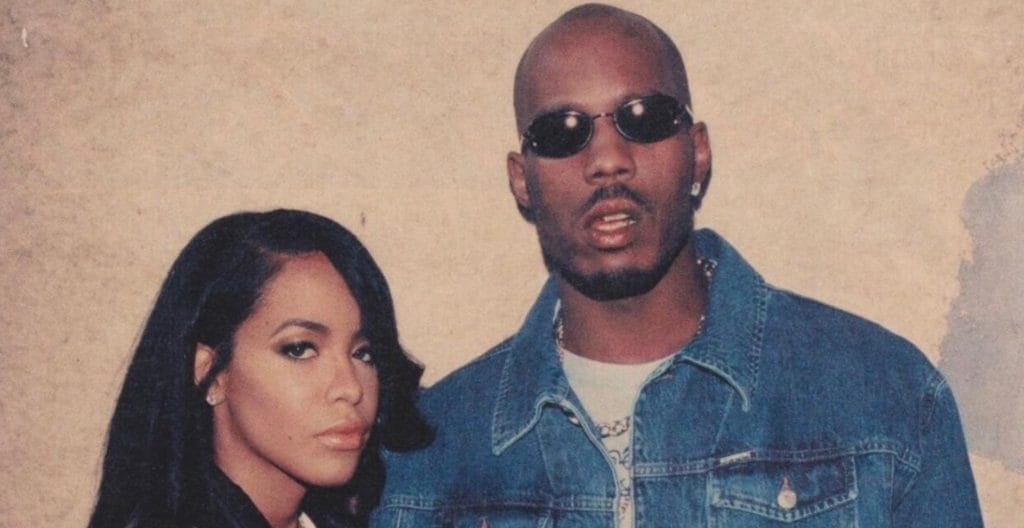

But, gliding past the important conversation of digital attribution and assignation of credit momentarily: once armed with this new availability, I started making producer playlists. One for Timbaland and Pharrell, one for Darkchild, one for DJ Premier, EZ Moe Bee, and so on. In playlisting for Timbo, I really sunk into the catalogs of his artists for the first time: Missy Elliott, Ginuwine, Magoo (pronounced: “mag-in-oo”.. i’m lost too, believe me), but most of all, “baby girl” Aaliyah and the back catalog of Blackground Records. Before her preternatural death at the age of 22, the princess of rnb/pop dominated movie soundtracks, albums, and remixes; Drake has sampled her, Missy and Timbaland take every chance they get to credit her with their careers, and rnb has patterned itself after her in image, vocal styling, and instrumentation.

Despite her contemporal prominence amongst the field, her pop cultural presence is dominated by her contemporaries (Beyoncé, Mary J. Blige, Mariah Carey, TLC, SWV, etc) Why? It’s likely to do with her uncle’s refusal to publish her catalog digitally (it’s not even available for purchase on iTunes), and the ignorance we all share to outdated modes of listening to music. To legally listen to Aaliyah, you’d need to find physical copies of now 20-year-old albums on tape or CD, and then find tape or CD-players to play them. There are, of course, less legal avenues to take. Most of her music is up on YouTube in some unofficial form or another, but no major platforms carry her music (and Blackground Records, her uncle’s company, loves taking things down). An artists’ legacy lies primarily in their recordings and hers may be forever lost in the transition of technologies.

Aaliyah’s catalog isn’t the only one slipping from our grasps: tapes/CDs/DVDs and performances epitomize much of our musical experiences. From old R&B promotional music videos to house shows in defunct clubs and old concert footage, we’ve already lost so much history to the embers of time. “You had to be there” moments fade as memories do, alongside the lost lives of the oldheads who hold those remembrances so fondly. Ephemerality is enjoyable, and poetic, but entails loss and heartbreak that capturing these moments elides; instead of losing events to the passage of time, we can savor their recordings.

YouTube as a platform serves as a saving grace of these recordings, as well as Instagram archive accounts like @ditc4eva94 which stockpiles old MTV Raps clips and interviews, live performances at The Tunnel, and a broad assortment of music-related content previously unearthed. YouTube and Instagram as corporations and content licensees, however, work against this squirreling away of cultural tidbits; the people who upload these bits don’t “own” the rights to their posts, which are quickly taken down in the name of copyright infringement and playing well with media partners (who wish to marketize history through re-releases, soundtracks, and documentaries). The perils of cultural commoditization reach backwards into the past, unfortunately. But why should they?

On the subject of the past…this commoditization rears its ugly head within the record labels and streaming services themselves, as new music begotten from the old suffers in the name of sample clearances. Samples of 70s/80s/90s rnb and soul records provide some of the most illuminative windows into the annals of Black records; producers from Pi’erre Bourne (yo Pi’erre, you wanna come out here?) to Q-Tip have heralded, used, almost abused the technique of cutting old records together to create rich soundscapes from familiar and obscure melodies alike. When Prince Paul went about crafting “Breakadawn” for De La Soul, for instance, he sought out the 1979 album cut “I Can’t Help It” from Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall: the grounded synths became a bassline upon which Posdnous and Trugoy’s vocals, a melody pulled from Smokey Robinson’s “A Quiet Storm”, and a line of keys from Blue Mitchell’s “Daydream”, were all foregrounded. These samples, and all samples used on De La Soul’s first six albums, were cleared for use from their original owners by De La Soul’s record label (Tommy Boy Records): Tommy Boy and De La Soul cut deals with all the artists and their labels to use their music on De La Soul’s albums, and pay the original musicians a percentage of the profits. However, they only cleared these samples for analog format release: CD, cassette tape, and vinyl LPs—but not for all formats in perpetuity. So, De La Soul couldn’t put their music up on streaming services, nor could their records be purchased via digital download. To add insult to injury, Tommy Boy finally cleared all of their music in late 2019 in preparation for a 30-year anniversary re-release of De La Soul’s debut album (3 Feet High and Rising) only to cut De La Soul out of their monetary gains by offering them a meager 10% cut of the proceeds. This story is reified in the difficulty artists have in clearing mixtapes (where samples were never cleared for tapes which were mostly promotional or off-the-books commercial products) for digital releases; classic music is lost to industry processes and bureaucratic notions of ownership.

Circling back, we must revisit digital attribution and credits. While music streaming giants have provided credits upon request and bundle many producer playlists to give legends their due, this process is woefully opaque and underdeveloped; Tidal remains the only streaming service to provide easily accessible and widespread album and song accreditation for songwriters and producers (Spotify’s coverage is shoddy at best), yet still it lacks liner note-quality of depth and story-telling once important to vinyl-purchasers and CD-hoarders. Beyond contributing to musicians’ legacies and histories, credits provide industry recognition and opportunities to the studio musicians and engineers behind all the great artists (whose work arguably make or break records); losing liner notes in digital music consumption means losing a layer of music history, and perpetuates an immediate loss in attribution and narrative-building. How do you tell the story of an album or artist without mentioning their producers, mixers and engineers, and writers? Jay-Z’s career is empty without the super-production he landed during his run at Def Jam, and his mixers, Guru and “Supa Engineer” Duro; J-Lo’s story can’t be told without Ashanti’s songwriting.

Underscoring all of this is the relatively under-wraps (yet colossally important) event of Universal Music Group’s master music recordings burning in 2008; hundreds of thousands of original recordings and demos were lost to an accidental fire in a Universal Studios storage lot, comprising much of the catalogs of music luminaries from Dr. Dre and Tupac Shakur to B.B. King, Janet Jackson, Joni Mitchell… A “master” recording comprises music as-first-lain-on-wax: losing a physical master is losing the music itself in its most untampered and highest fidelity format, to say nothing of the struggles artists have fought to own their own “lost” recordings (many of which have now gone up in smoke). Music’s fundamental ephemerality is reinforced by such activity.

This is ultimately a story of loss; maybe I’m more personally invested in history than is healthy but losing culture, indefinitely, is a heavy emptiness. Preservation, akin to curated museums, is possible; but a fast-moving industry always scouring the next medium for the next brand-spanking-new hit cannot be trusted with retaining its own history, it seems. So this is also a call to arms: for piracy, but more importantly for the grander establishment of media commons such that public ownership and rights to view and use content prevent the corporatized disappearance of important and unimportant music alike; and for history-telling, incorporated into records via endless think-pieces and social media posts as well as an expansion of credits available online. We’ve already lost so much; we needn’t let the things we enjoy, cherish, and create, fall away like the embers from a decaying cigarette into the ashtray of time’s abyss.